“Did you have any adventures outside at school today?”

This is a question children are more apt to more respond to readily than the traditional query “What did you do at school today?” The term adventure can activate memories of many different activities occurring throughout the day, when children are free to explore the natural world outside their classroom. When adult alumni visit our campus, they always grow animated sharing wistful stories about the magical play they had on the hillside or big field.

The school has always encouraged children to find fulfillment in nature by creating many different school terrains to actively explore, and we are always developing new ones.

A weekend walk on campus is a happy way to encourage your child to talk in more detail about experiences at school. Some areas, like the preschool yards and Seven Circles Garden, are locked for safety, but other fun spaces are open for your family to come and play in. Meandering through the school grounds with children encourages them to feel a sense of belonging throughout the whole school.

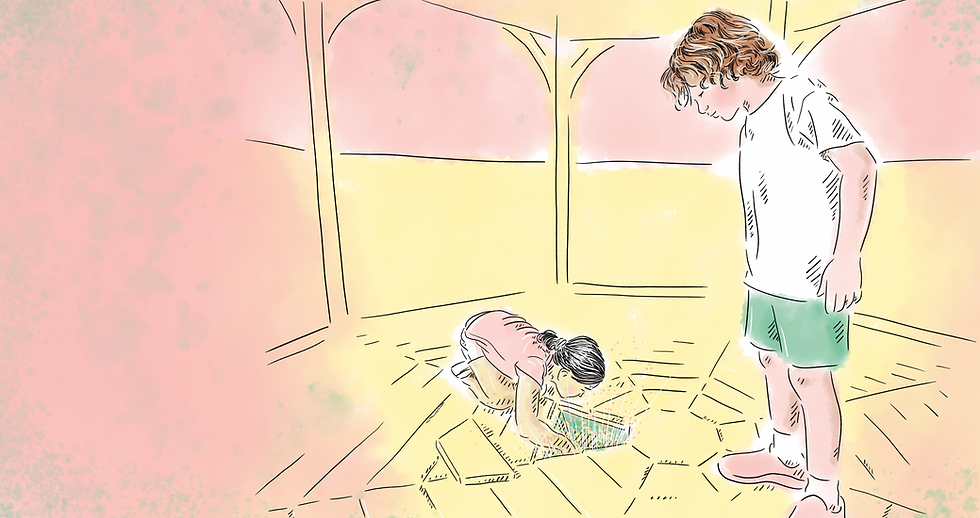

Walking up the central steps, the Children’s Garden, on your left, runs in front of Rooms 3, 4, and 5. Its little bridge and arch seem to lead to another world, with its manzanita forest and gazebo. The rose garden and pampas grass are open weekends for families to enjoy, but for now the area beyond the arch is only for teachers and their classes.

Turning right on the first tier, the Preschool Garden, in front of Rooms 1 and 2, is fenced and closed, but you can peer in and ask your child what jobs they do in the garden. You can see the children’s watering cans and gardening tools, the lush plants, and the squash the children have planted.

Further down the first tier on the right, stop and marvel at the new field of wildflowers planted earlier this year (see above). It is often filled with birds and butterflies. Across from the wildflowers, on the left, is a vibrant garden of succulents.

Walking along the second tier, you can look down at the two preschool yards and get an overview of all different parts of both yards. Your child might want to point out favorite places to play, ride bikes, dig castles in the sand. There are sandboxes, a playhouse, climbing structures, and several flourishing mini-gardens that children water in both gardens. In the Rooms 3, 4, and 5 yard, notice teacher Max Reif’s magical mural on the gazebo cabinets, depicting scenes suggested by the children.

Behind Room 7 and 8, the kindergarten yard is open on the weekend. It contains several areas—bushes on the hillside where children can nestle and play, a special little fenced area above the pretend kitchen with sea shells and beautiful rocks, and a new garden, formerly the chicken coop, now under construction by children. Please don’t touch the tools or wheelbarrows.

Walking up the path from the big playground to the big field, the organic Seven Circles Garden, set along the hillside, hosts more magical experiences than any other on campus, as well as comprehensive learning in elementary science. You can walk along the fence surrounding this huge farm-like space until you reach the top of the hill. Ask your child about the edible flowers, the blackberry bushes, the beehive, the guinea pig cage, the quail roost, and the magical place in the gazebo where fairies are purported to emerge through a special opening.

We are so grateful for our spacious campus and especially to our gardening teacher, Adrienne Wallace, and to all the children and parents who help us keep all our nature terrains flourishing.